The American housing market is often described as an escalating crisis – prices soaring to unreachable heights, dreams of ownership slipping further out of reach (which is truth). But what if the story could look somewhat different when told through the lens of something as ordinary as a Big Mac?

The Big Mac Housing Index from InvestorsObserver peels back the curtain on housing affordability by asking a deceptively simple question: how many burgers does it take to buy a median-priced home in the U.S. today?

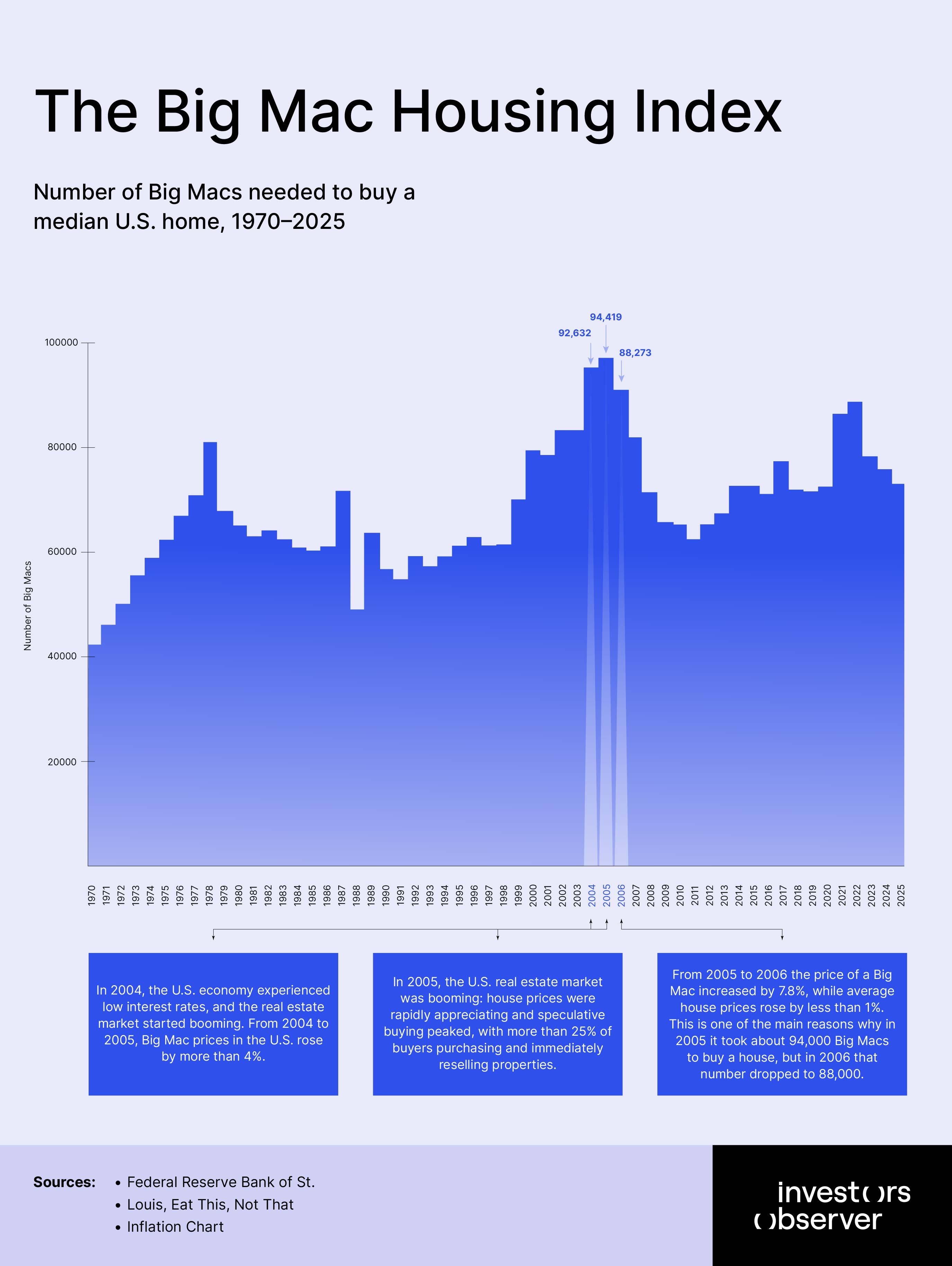

Despite headlines of ever-rising home prices, the Big Mac Housing Index shows that in 2025, Americans need fewer Big Macs to buy a home than they did during the 2005 peak of the real estate bubble.

This suggests that when adjusted for the rising cost of everyday goods, housing has become relatively more accessible – not less.

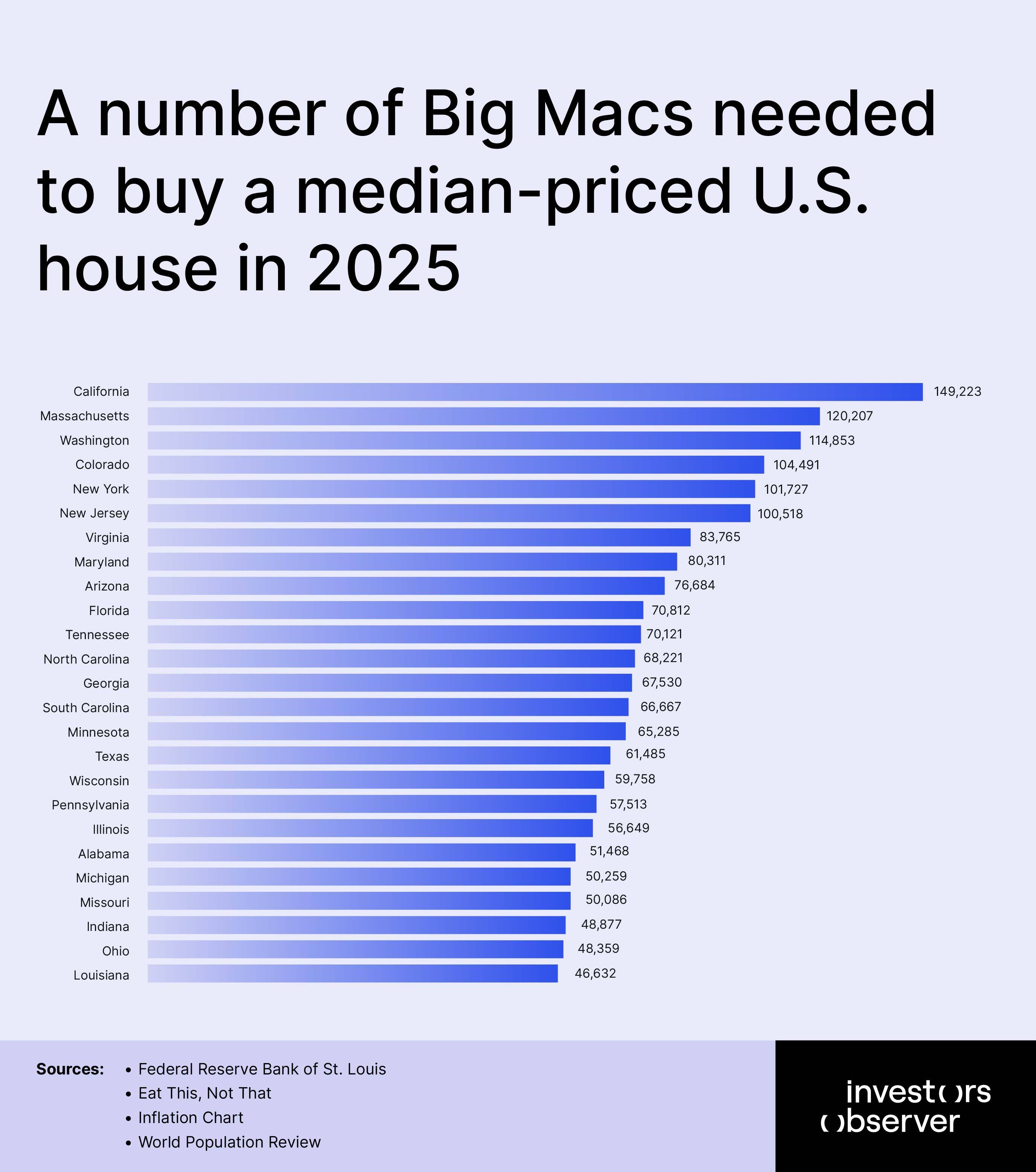

Yet, the cost of the American dream varies drastically by state – from California’s 149,000 burgers to Louisiana’s 46,000 – showing deep geographic inequality.

Key findings

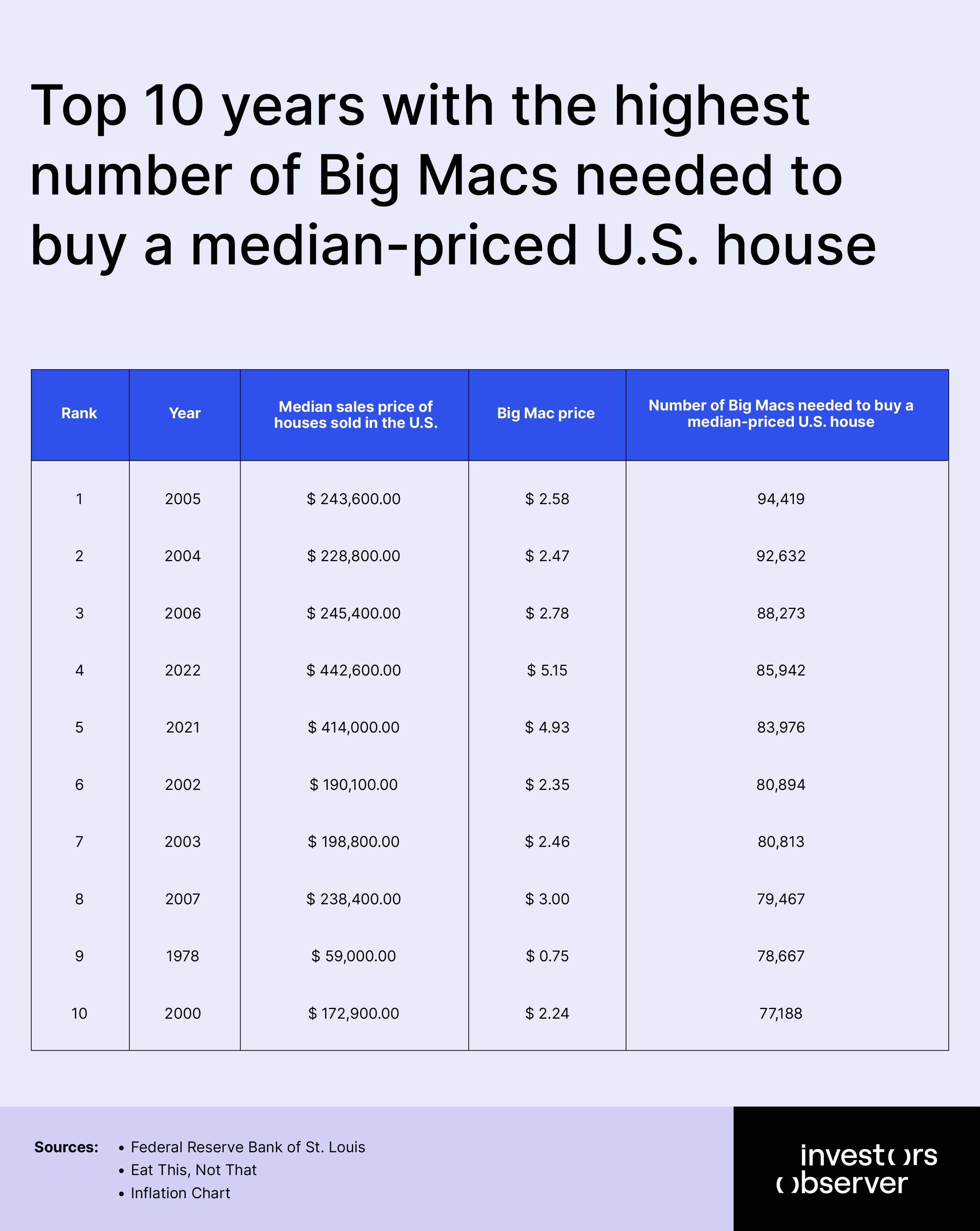

- In 2005, it took approximately 94,419 Big Macs to buy a median-priced house in the U.S., the highest point recorded in the dataset.

- The average number of Big Macs needed to purchase a house in the U.S. from 1970 to 2025 is about 66,379 Big Macs.

- By 2025, the number of Big Macs required to buy a median-priced house dropped to roughly 70,950 Big Macs, down nearly 7% from 2022.

- California is the most expensive state for housing in 2025, requiring about 149,223 Big Macs to buy a median-priced home, while Louisiana is the most affordable with about 46,632 Big Macs needed.

- From 2022 to 2025, median house prices in the U.S. decreased from $442,600 to $410,800, while the average Big Mac price increased from $5.15 to $5.79, contributing to a decline in the index value.

The 1970s: affordable homes and cheap burgers

In the 1970s, the housing market in the U.S. was relatively balanced when measured against consumer prices like the Big Mac. In 1970, the median house price was $22,600, while a Big Mac cost $0.55, resulting in about 41,091 Big Macs needed per house.

Over the decade, inflation pushed home prices and burger prices higher, but at different rates. By 1978, a median house cost $59,000, and a Big Mac was $0.75, with the index rising to about 78,667 Big Macs.

The biggest jump occurred after 1976, with the index moving from 65,000 Big Macs in 1976 to nearly 79,000 Big Macs just two years later. The steady rise is mainly because housing prices more than doubled through the decade, while the Big Mac price increased only marginally.

This pattern means that for the average American, the ability to buy a home became tougher if both salaries and burger prices are viewed as proxies for general income and everyday purchasing power. The average for the decade hovered between 41,000 and 78,000 Big Macs per house, often at the lower bound in the early years.

The index ends the decade at its highest, emphasizing the increasing challenge of homeownership at the time, despite popular perceptions of the post-war years as more affordable. This reveals how quickly affordability can shift, even before more recent housing booms.

The 1980s: rising costs and housing demand

The 1980s brought volatility to the Big Mac Housing Index. In 1980, a house cost $66,400 and a Big Mac $1.05, with an index of 63,238 Big Macs. While burger prices rose through the decade, so did housing, but with more dramatic shifts.

By 1988, the cost of a house was $113,900 and a Big Mac $2.39, which results in about 47,657 Big Macs. This drop from the early decade reflects a period of relatively higher wages or slower home price growth in the mid-1980s.

However, the index wasn’t stable. In some years, such as 1987, the number was notably higher, at 69,687 Big Macs. Fluctuations in this decade can be attributed to rapid changes in mortgage rates, inflation cycles, and policy shifts, which made home prices unpredictable.

The median fluctuated mostly between 47,000 and 69,000 Big Macs, giving Americans some years of relative affordability and others with much less. The general trend was a slight decrease in the number of Big Macs required, pointing to improved or stabilized affordability and indicating that incomes or cost-of-living adjustments may have kept pace with property prices in some periods.

The 1990s: stability with slight gains in affordability

The 1990s saw a period of moderate stability in the Big Mac Housing Index. In 1990, a median-priced house cost $121,500 and a Big Mac $2.20, making the index 55,227 Big Macs. Prices for both homes and burgers continued to climb, but housing prices did not surge as dramatically as in earlier decades. By 1999, the index was 68,025 Big Macs, with a house costing $165,300 and a Big Mac $2.43.

Most years in this decade ranged between 53,000 and 68,000 Big Macs per house, showing that Americans could broadly predict their purchasing power for homes. The index’s upward creep late in the decade suggests housing started to outpace burger price inflation again, possibly due to speculative buying in anticipation of future growth.

The steady but modest increase implies that more families could manage a home purchase without suffering sudden affordability shocks. On average, the index offered a sense of normalcy and predictability that contrasted with the early volatility of the 1980s. The decade closed with a small upward trend, laying the foundation for the housing surge in the 2000s.

The 2000s: the housing bubble peaks

This decade is dominated by the housing bubble, which is clearly visible in the Big Mac Housing Index. Entering the millennium, a house cost $172,900 and a Big Mac was $2.24, with the index at 77,188 Big Macs. Both prices continued rising, but home prices soared much faster.

By 2005, the bubble’s peak, it cost 94,419 Big Macs to buy a house—the highest in the dataset. This was driven by rapid and widespread price appreciation across the real estate market, speculative buying, and accessible credit.

Big Mac prices did increase (from $2.24 to $2.58 by 2005), but not nearly enough to match the jump in home prices. The aftermath of the bubble saw the index fall from its peak; by 2007, it was down to 79,467 Big Macs, and it would continue falling following the housing crisis.

Americans in this decade faced the widest gap between consumer prices and property values seen in 50 years. The index not only tells the story of unaffordability, but also how quickly conditions can change. Policymakers and families alike could use this as a warning sign, as sharp increases signal overheated markets and growing risks for home buyers.

The 2010s: recovery and slow improvement

In the 2010s, the index paints a picture of slow recovery and moderate improvement in housing affordability. In 2010, the median home cost was $224,300 with a Big Mac at $3.53, making the index 63,541 Big Macs. By 2019, the count was around 69,448 Big Macs for a $327,100 house and a $4.71 burger.

This decade saw gradual, steady increases in both home and Big Mac prices, although neither spiked like in the previous boom-and-bust cycle. The index hovered in the mid-60,000s, only occasionally breaching 70,000. This means the cost of homeownership for most Americans did not undergo dramatic shifts during these years; families could plan with more confidence.

The stability also reflects an economy climbing out of recession, with home prices rising but balanced by wage growth and broader inflation. This period provided some breathing room for buyers, as the challenge of homeownership grew only slowly.

The 2020s: inflation and market fluctuations

Current data from the 2020s shows how inflation and recent price corrections have affected the Big Mac Housing Index. In 2020, a house cost $338,600 and a Big Mac was $4.82, with an index of 70,249 Big Macs. By 2022, the home price surged to $442,600 and a Big Mac to $5.15, giving an index of 85,942 Big Macs.

But the following years tracked a correction in home prices and further consumer inflation: in 2025, a median house was $410,800 and a Big Mac $5.79, dropping the index to 70,950 Big Macs – down nearly 7% from 2022.

In the most recent data, California is the most expensive state, needing 149,223 Big Macs for a house, while Louisiana requires just 46,632 Big Macs. The average for the top 25 states in 2025 is 74,860 Big Macs. This shows stark geographic variation in affordability.

The decline in the index since 2022 reflects disinflationary pressures in housing while consumer goods, including the Big Mac, continue to become more costly. Everyday Americans now face affordability challenges once again, but not as severe as the mid-2000s. The index reveals how shifts in inflation and market corrections affect real purchasing power quickly and tangibly.

Big Mac Housing Index 2025: homes cost less burgers than 2005 peak but remain steep

In 2025, the American housing market shows major regional differences. On the high end, Californians face the steepest burger bill. With a median home price of $864,000 and a Big Mac costing $5.79, it takes 149,223 Big Macs to purchase a typical Californian house. That's nearly double the average for the nation’s top 25 states.

Massachusetts and Washington also rank among the least affordable, demanding 120,207 and 114,853 Big Macs respectively. These figures show entrenched challenges in the most populous and economic powerhouse states, where the American dream often demands deep pockets.

Meanwhile, affordability improves markedly in other corners of the country. Louisiana, at the low end, requires just 46,632 Big Macs to buy a house – less than a third of California’s figure.

States like Ohio, Alabama, and Indiana also offer comparatively accessible markets, with Big Mac counts hovering around 48,000 to 50,000. These contrasts paint a vivid map of opportunity and strain, with some states offering genuine homeownership chances and others locked in high-cost housing traps.

States in the middle – Texas, Florida, and Georgia – show more moderate figures around 61,000 to 68,000 Big Macs, reflecting markets still within reach for many Americans. New York and New Jersey stand out with higher burger counts above 100,000, illustrating affordability pressures in major metropolitan regions.

Lessons from the Big Mac Housing Index

The data shows the significant regional disparities in housing affordability. For example, in 2025, buying a median-priced home in California requires around 149,000 Big Macs. That is more than double the national average of about 70,000 Big Macs needed across the country.

Contrast this with Louisiana, where just under 47,000 Big Macs are enough to purchase a median home. This wide gap signals that affordability is deeply concentrated and suggests that many Americans are effectively priced out of certain markets.

Buyers looking for value should consider states like Ohio, Louisiana, or Alabama, where housing remains within reach relative to the cost of everyday goods.

The index also reveals a notable shift starting in the early 2020s. After hitting a peak near 94,000 Big Macs per house in 2005 during the housing boom, the index declined with the market adjustment but then rose again, reaching over 85,000 Big Macs in 2022.

By 2025, the ratio dropped to about 71,000 Big Macs, reflecting both a fall in median home prices and a steady rise in consumer prices. This pattern suggests that while housing costs can be volatile, inflation in consumer goods like burgers also reshapes real affordability.

Buyers and policymakers need to watch not just housing prices, but how these prices relate to broader inflationary trends affecting everyday expenses.

The scale of these numbers implies that homeownership in many parts of the country demands the equivalent cost of tens of thousands of meals. Framing housing affordability in this relatable way reminds stakeholders that buying a home remains a substantial financial commitment, often many times larger than simple consumer purchases.

This perspective could inform financial education, helping potential buyers understand the scale of their investment relative to daily expenditures.

Finally, the index’s long historical view offers a cautionary tale. The ballooning cost ratio before the 2008 crisis signaled rising risks in the market. Similar spikes at the state or national level today could be an early warning signal to moderate price growth or bolster housing supply.

It also shows the importance of balancing inflation in housing with wage growth to maintain accessibility.

Methodology

This analysis of the Big Mac Housing Index combines historical housing price data with consumer price data to create a simple and relatable measure of housing affordability across time and regions in the U.S.

Median Sales Price of Houses

Annual median home sales price data were collected for the U.S. from 1970 through 2025. National data was gathered quarterly and aggregated for year-end values to ensure consistency. State-level median house prices for 2025 were sourced from recent real estate market reports for the largest 25 states.

Big Mac Prices

The price of a McDonald’s Big Mac was used as a proxy for everyday consumer costs. Historical Big Mac price data corresponding to each year from 1970 to 2025 were compiled from inflation tracking sources and adjusted where necessary to reflect average U.S. prices at year-end. State-level 2025 Big Mac prices used uniform pricing from June 2025 for comparison.

Calculation

The core calculation for the Big Mac Housing Index is a simple ratio:

Big Mac Housing Index = Median sales price of houses / Big Mac price

This ratio represents the number of Big Macs one would need to purchase to equal the cost of a median-priced home in a given year or location. For example, if the median house price is $410,800 and a Big Mac costs $5.79, the index value is approximately 70,950 Big Macs.

Limitations

The index is a relative affordability measure and does not consider income or wage data directly, focusing instead on the shifting relationship between home prices and a common consumer good over time.

Pricing variations across regions and stores exist, but the use of Big Mac prices aims to standardize consumer cost comparison given the product’s widespread availability.

Housing market fluctuations influenced by local markets, credit availability, and economic cycles are encapsulated only through median prices and are not dissected by sub-market segments.

Sources

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

- Eat This, Not That

- Inflation Chart

- World Population Review

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are markedmarked