Canada's ability to push back against Trump-era tariffs is imited, and one big reason why is its deep financial dependence on the United States.

The country’s largest pension manager, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), has nearly half its assets tied up in the U.S., according to its latest annual report.

As of March 31, the CPPIB had parked 47% of its $714 billion portfolio in American stocks, bonds, and private deals. That’s up from 36% just two years ago.

Meanwhile, only 12% of its portfolio is invested in Canadian assets.

Before the trade war, the U.S.-heavy portfolio looked like a smart call. The fund notched a 9.3% return in its last fiscal year, driven by strong gains in stocks, credit, and private equity.

But the mood has shifted since, especially after Trump suggested Canada should consider becoming the 51st U.S. state.

That remark, flippant or not, sent a message. Canadian business leaders quickly called on lawmakers to rewrite pension rules and push more capital into homegrown investments.

That’s easier said than done because the U.S. simply offers more scale and liquidity

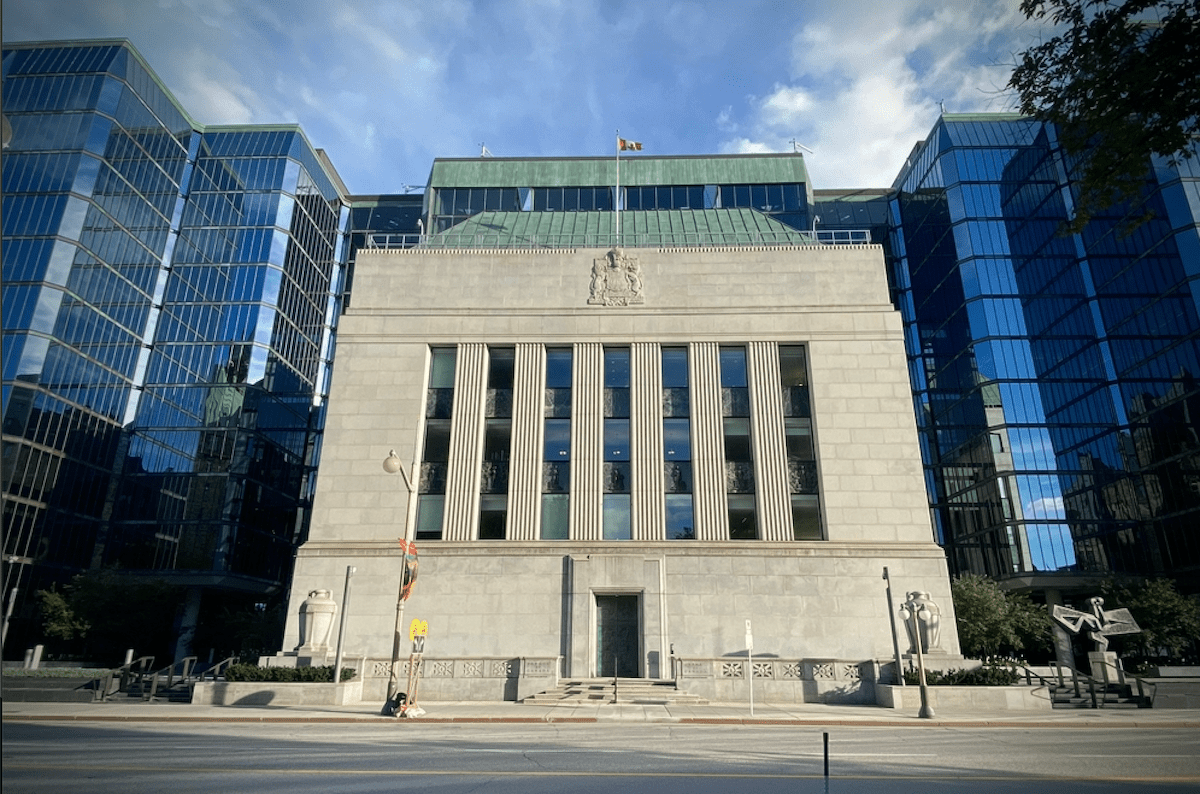

According to Bank of Canada research, American fixed-income markets are 32 times the size of Canada’s.

The U.S. accounts for nearly half the global corporate bond market, while Canada only for a mere 1%.

That size matters when it comes to institutional money.

As BoC researchers put it, “Large-market countries like the United States are better able to take advantage of economies of scope and scale.”

U.S.-Canada trade may never be the same

The U.S.-Canada trade fight has already reshaped economic strategy on both sides of the border.

After the U.S. slapped a 25% tariff on most Canadian goods — including a 10% duty on energy — Ottawa hit back with its own 25% tariffs on $20 billion worth of U.S. exports.

The retaliation slowed cross-border trade and pushed Canada to explore new deals elsewhere. But those efforts may not go far enough to protect the economy.

Oxford Economics reports that Canada has now paused most of its countermeasures.

The move came after Prime Minister Mark Carney granted a six-month exemption on U.S. products critical to Canadian manufacturing.

“It’s a strategic play on the government’s part to avoid damaging the Canadian economy,” said Tony Stillo, director at Oxford Economics.

The reality is, Canada may not have much leverage. Roughly 75% of its exports go to the U.S., according to official data.

When your largest customer also controls the world’s deepest capital markets, there are limits to how hard you can push back.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are markedmarked